'The Russian Language Has Profoundly Changed My Life'

Rafael Guzmán Tirado, Doctor of Philology, Professor of the Department of Greek and Slavic Philology at the University of Granada, Spain; founder of the first department of Slavic studies in Spain, and expert in Russian and Spanish philology. Since 2024, Rafael G. Tirado has taught an advanced Spanish course in the bachelor's and master's programmes at the HSE School of Foreign Languages. In this interview, Rafael G. Tirado shares his insights on the essence of true vocation, the ways in which knowledge of foreign languages and cultures broadens one’s appreciation of human achievement, and the qualities that make Russian students unique.

— When did you first develop an interest in learning foreign languages?

— I fell in love with foreign languages while I was still in school. I must say I was fortunate—my generation was the last to study French in Spanish schools. I loved French and later Latin for being synthetic languages. In my final year of school, English was introduced, and after graduating from university, I spent ten years teaching English and French in secondary school. That was before I discovered my passion for the Russian language.

— What do you enjoy most about your profession?

— The fact that I get to do what I love. Confucius once said: 'Choose a job you like, and you won't have to work a single day in your life!' I’m fortunate to be engaged in something I love and adore—the Russian language and languages in general. For me, this isn't just a job; it's my passion.

— You are fluent in five foreign languages: English, Russian, French, Italian, and Chinese. Is it true that the more foreign languages a person speaks, the easier it becomes for them to learn each additional language?

— Of course, it's true. Some issues encountered while learning one language will reoccur when learning others. This is especially true for languages within the same language family. It’s one thing to learn French, Italian, and English; it's another matter when you learn, for example, Russian and Chinese. That is a whole different story. For example, tones in Chinese are difficult for native speakers of languages that don't have this feature.

— When did you first become interested in learning Russian, and why?

— I remember the moment clearly. I was 17 years old, and I vividly recall that on that day in the city where I lived, Linares, the film Doctor Zhivago was playing. Everything in that film was so beautiful: the story, the music, the atmosphere, and Russia itself. It was only later, however, that I discovered it was filmed outside of Russia. But these factors—the film Doctor Zhivago, my love for Latin as a synthetic language, and the fact that by then I had already read much of Russian literature in Spanish—all came together. At 18, I started learning Russian using a self-study book. This language captivated me, and I began to dream of travelling to Russia.

My parents also really wanted to visit the Soviet Union. When I was 22, I was able to give this gift to my parents with my first paycheque: in 1979, the three of us travelled to the USSR and visited Moscow and Leningrad. By then, I had already fallen completely in love with the country and began searching for an opportunity to come here to study. That opportunity came when I was 32, and I travelled to Russia to pursue a doctoral programme at Moscow State University.

I never expected my life to change so profoundly after that, which I’m very grateful for. After returning to Granada, my hometown, the rector of the University of Granada asked me to establish a department of Slavic studies—which I have been engaged in ever since. And, as I mentioned earlier, it doesn’t feel like work.

I adore the Russian language, but I also have a deep love for my native language and culture. Therefore, in addition to Russian, I also teach Spanish. I would say that these two languages complement each other really well.

— How quickly were you able to learn Russian?

— I started studying Russian in earnest quite late. Before my studies in the USSR, I had been learning Russian in Spain using a self-study book, but that's not an effective way to learn a language. So, when I arrived in the USSR for the doctoral programme at Moscow State University, I barely spoke any Russian, and it was very challenging.

But I decided that since my dream had come true—I had come to the USSR to study Russian with a scholarship from the Soviet Union—there was no turning back. I knew I had to make the most of the opportunity and devote all my efforts to learning the language.

I started attending every single class in Russian philology from morning to evening because, at that time, such subjects were not taught in Spain. After four years of intensive study, I can say that I practically mastered Russian.

Rafael G. Tirado's contribution to promoting the Russian language and preserving and popularising Russian culture over the past 30 years is immense, as evidenced by numerous awards, including the Pushkin Gold Medal from the International Association of Teachers of Russian Language and Literature (2006), the Order 'In the Name of Life on Earth' from the Embassy of the Russian Federation for promoting the Russian language (2007), and the Honorary Badge of Rossotrudnichestvo 'For Friendship and Cooperation' (2015).

On November 4, 2017, Rafael Guzmán Tirado was awarded the Order of Friendship for his contributions to the preservation and promotion of Russian culture in Spain. The decoration was presented to him in the Kremlin by Russian President Vladimir Putin. In 2021, Rafael G. Tirado was granted Russian citizenship in recognition of his exceptional services to the Russian Federation.

— You have lectured in many countries around the world. Does the approach to teaching foreign languages and cultures differ from country to country?

— Of course, it differs. I personally experienced the rigorous Soviet language-learning methodology, and it produced excellent results. Thanks to the courses I took, I was able to write and defend my dissertation in Russian as successfully as I would have in my homeland.

When we opened the Department of Slavic Studies at the University of Granada in 1991, Soviet students particularly amazed us with their profound training. I visited numerous universities in Russia and the Soviet Union, and nothing has changed in this regard since then. The Soviet Union had the largest Spanish studies programme in the world, which is highly significant.

I have extensive experience teaching languages. At the University of Granada's Modern Languages Centre, I taught Spanish to foreign students from all over the world for many years. I also teach Spanish in Russia and have been teaching Russian as a foreign language for 30 years. I can say that the modern teaching methodology practiced in Russia is very profound.

I believe that anyone who works with Russian students, whether in Spain or here in Russia, can clearly see the serious work and methodology behind their learning. The Soviet education system, along with the modern Russian education system, guarantee high quality. And what I am witnessing at HSE University perfectly confirms this.

— What are your impressions of working at the School of Foreign Languages at HSE University? Are Russian students different from students in other countries?

— Russian students are distinguished by their dedication to learning, as I have observed. I have been working for a long time with both Russian students and those to whom I teach Russian as a foreign language. What particularly struck me during the weeks I’ve been teaching at the HSE School of Foreign Languages was the students' proficiency in Spanish, their excellent knowledge of Latin American culture, and their understanding of the cultural specifics of modern Spain and Latin America.

And this is no small feat, considering that the students are still very young. Of course, thanks to the internet, accessing information has become much easier now. When I started learning Russian, we only had radio, and I would search for the right station at night to learn things. But one needs to know how to properly use the tools provided by the internet and how to work with all the available information. After all, every country has its pros and cons. I found that Russian students, on one hand, have a very realistic view of Spain and the Spanish-speaking world, while on the other hand, this view is very positive. I am sure that their teachers deserve credit for successfully conveying this aspect to their students.

I will never forget the enthusiasm with which students of the HSE School of Foreign Languages speak about Spain and the Spanish-speaking world, as well as their sincere desire to travel to Spain and explore the entire Spanish-speaking world—we are a vast community of 500 million people. These students already have a fairly deep understanding of our culture and artists. They are clearly receiving a well-rounded education, and behind this achievement is the hard work of the entire team at the HSE School of Foreign Languages.

One can simply speak a language well, but behind every language lies a great culture. This is something that unites us as well—the pride our peoples take in their culture. Now that Russia has prioritised developing contacts with Latin America, I believe our students are well-prepared to take on the tasks that will be set for them.

— With your active support, the University of Granada has regularly hosted academic and educational events showcasing Russia's cultural and historical heritage. Have any of these events become a tradition?

— I would highlight three key events. First, in 2015, we successfully organised the XIII Congress of the International Association of Teachers of Russian Language and Literature (MAPRYAL) in Granada. Lyudmila Verbitskaya, for whom I have immense respect, was the president of MAPRYAL.

The congress brought together 1,200 participants from 60 countries, marking a historic moment for Russian Studies at the University of Granada and in Spain, placing them in the annals of global Russian studies. The Russian government gifted us a bust of Alexander Pushkin, which now stands in one of the central parks in Granada.

Another significant event we have been hosting in recent years is a series of seminars and conferences on contemporary Russian literature.

There is clear evidence of a strong interest in contemporary Russian literature in Spain today. For example, I believe that last year, Guzel Yakhina's novel Zuleikha was published in Spanish for the fourth time.

I am also proud that my Spanish translation of Laurus by Eugene Vodolazkin has been republished for the third time. I am happy to have translated this book, which is in demand not only in my country but across the entire Spanish-speaking world. This novel has been translated into 35 languages.

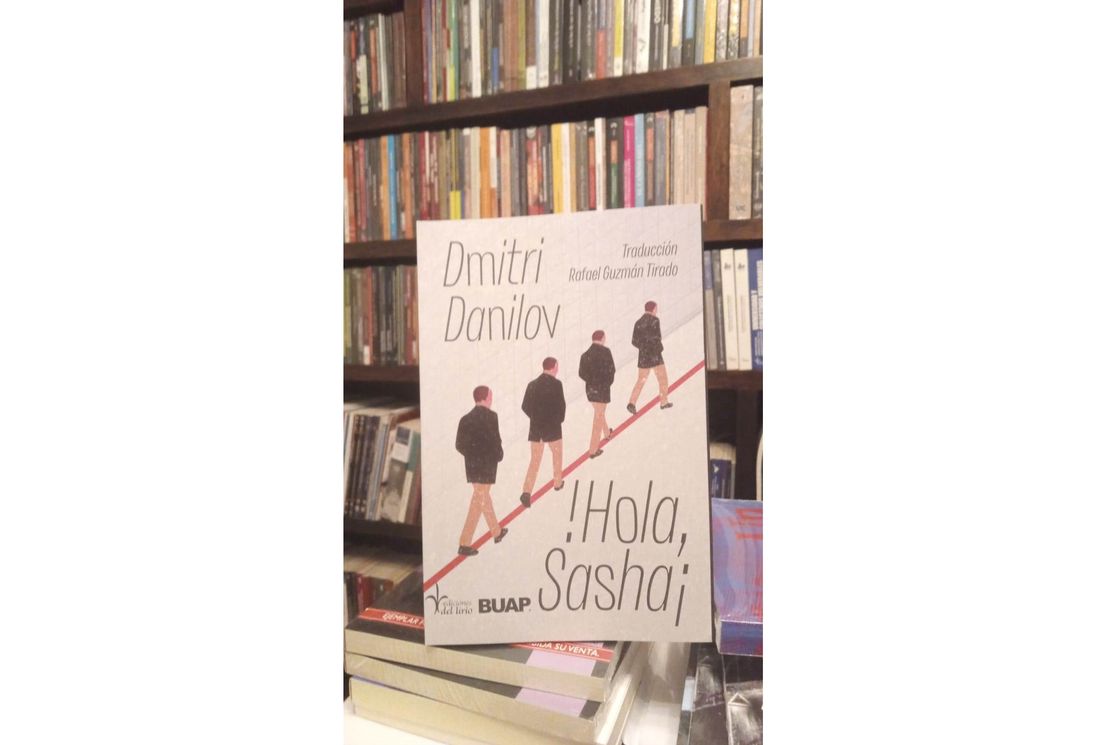

As I attend translator conferences and literary forums in Russia, I am always on the lookout for new works that could be introduced in Spain and Latin America. For example, just yesterday in Mexico, my translation of Dmitry Danilov's wonderful book Sasha, Hello! was published. I am very glad that the Spanish-speaking audience will now have the chance to read such an amazing book. I am confident that contemporary Russian literature will continue to be in high demand in the Spanish-speaking world.

As for the classics, interest in them is guaranteed. I am impressed by how new translations of Russian classical literature continue to emerge. This is a remarkable phenomenon, which I emphasise during my lectures with students. For example, I recently joined the jury of Read Russia, an award for outstanding translations of Russian literature into foreign languages, and I was amazed to learn that five years ago, yet another translation of Anna Karenina won the award. Interestingly, native Russian speakers will only read the single original version of the book. But the magic of Russian literature and the art of translation lie in the fact that each generation seeks its own version of the translation. It is clear that translations become outdated over time, and this applies to translations of all world literature. But this trend of new translations of classics emerging is unique to Russian literature. One might wonder, if translations already exist, why translate again? This means that society values and needs it.

We also host events dedicated to Russian writers and poets, such as the Marina Tsvetaeva Days, which were held in a hybrid format despite the pandemic.

All these events laid the foundation for the development of Russian studies not only at the University of Granada but also across Spain as a whole.

— What is your favourite book, and why? Is there a book that you could read over and over again?

— My favourite writers, even before I fully discovered Russian literature, were Ilya Ilf and Yevgeny Petrov. I know The Twelve Chairs and The Little Golden Calf almost by heart, as they are my favourite books. It was after reading them that I developed a taste for satire. By that time, Ilf and Petrov's books had already been translated into Spanish in Cuba. I can't imagine what it must have taken to translate such a masterpiece, with all its subtext. I always advise my students to read Ilf and Petrov, as their works contain many expressions that have become famous and without which it would be impossible to understand a third of Russian colloquial speech.

— You have translated stories by Mikhail Zoshchenko and novels by Eugene Vodolazkin into Spanish. Could you share your experience of this?

— Although I have been teaching translation theory and the translation of official documents at the University of Granada for 30 years, I only started translating fiction relatively recently—just five years ago, despite having wanted to translate it for a long time.

When I was in the doctoral programme at MSU in the late 80s, books began to emerge that had not been available before. I remember getting my hands on Arkady Averchenko's stories. I bought this book right at MSU and kept thinking that I would translate it someday. It was only recently that I actually translated it, and, of course, the book is highly popular in Spain.

Then a publishing house, which later also published the translations of Eugene Vodolazkin's books, suggested that I translate stories by Mikhail Zoshchenko. The director of that publishing house said that he had read them in English and would like to know how they would sound in Spanish. Of course, it is not easy for the young Spanish-speaking audience to understand some aspects of life in Soviet society at that time, but I am still proud that I was able to make this small contribution to the translation of Zoshchenko's works.

When it comes to contemporary authors, I absolutely adore Eugene Vodolazkin. I have translated most of his works into Spanish, except for his most recent one, including Laurus, The Aviator, Brisbane, and A History of the Island.

Another outstanding contemporary writer is Dmitry Danilov, and I was delighted to translate his book Sasha, Hello!.

I truly enjoy working as a translator because it allows me to promote excellent literature in our countries and introduce it to the Spanish-speaking public. Fluency in foreign languages is an invaluable skill. Some say it’s like living multiple lives, and I couldn’t agree more.

Knowledge of foreign languages and cultures reveals the magic of all human achievement. For example, in music, I would love for as many people as possible to discover masterpieces like the famous waltz from My Affectionate and Gentle Beast or Sviridov's waltz from Musical Illustrations to Alexander Pushkin's The Snowstorm.

I am also proud to have been introduced to Soviet cinema, such as the comedies, without which it is impossible to fully understand the Russian language and culture. I strive to share all of this with my students.

— Which cities in Russia have you had the chance to visit?

— When I was a doctoral student, I had the opportunity to travel to Yakutsk. I have visited the Caucasus many times, including Nalchik, where I defended my doctoral dissertation. I had defended my PhD dissertation in Moscow. I set myself the goal of reaching Vladivostok in August of this year. I definitely want to visit Sakhalin someday. Therefore, there is still much to look forward to. It would take a couple of lifetimes to travel around such a vast country as Russia.

— You are a multifaceted and talented individual. Many people would dream of achieving even a fraction of your accomplishments. Could you share some advice on how to achieve success?

— Choose to do something you truly enjoy. I could have retired eight years ago. Yet I continue working because it doesn’t feel like work to me. If I retired, I would have to stop doing what I love. Therefore, as long as I have the energy, I will continue doing what I enjoy, such as teaching Russian and Spanish, and promoting both Russian and Spanish cultures.

You can watch the interview video (in Russian) here.